Olga Carolina Rama, la grande artista torinese conosciuta come Carol Rama ci ha lasciati. Le avevamo dedicato un articolo su D’ARS nr. 219 in occasione dell’uscita del volume “Carol Rama. Il magazzino dell’anima”, un viaggio nella sua casa che non è soltanto una dimora o uno studio, ma il luogo in cui ha vissuto per settant’anni, accumulando una quantità inimmaginabile di oggetti affettivi, alcuni provenienti dalla famiglia, altri feticci raccattati in ogni dove, altri regalati da amici (tra i quali Man Ray, Carlo Mollino, Andy Warhol, Edoardo Sanguinetti), tutti disposti in un ordine maniacale all’apparenza caotico, come ogni opera d’arte che ne valga l’appellativo…. è così che vogliamo ricordarla

Detesto i fiori, forse perché sono più belli dei miei quadri, più belli di me. Per un’ira che ho dentro.

(Carol Rama)

Olga Carolina Rama, Torino, 1918. Così all’anagrafe. Nei primi acquerelli Olgacarolrama, lettere sposate in minuscolo, pacate, quasi flemmatiche. Nel giro di pochi anni solo Carol Rama, nome d’arte, risolto e asciutto, che ha sollecitato l’attenzione di molti, da Man Ray a Paolo Poli, il quale scrive “mi è sempre piaciuto questo nome, con delle ascendenze direi greche, come panorama, cinerama”. Carol Rama è artista di spicco del Novecento italiano, donna eccentrica e tenace, dalla feconda visionarietà, eppure sempre ardentemente legata alla realtà. Una realtà filtrata e circoscritta alla sua biografia, nella quale fantasmi e oggetti sono congiunti e combinati nella creazione di un immaginario complesso, nudo e crudo.

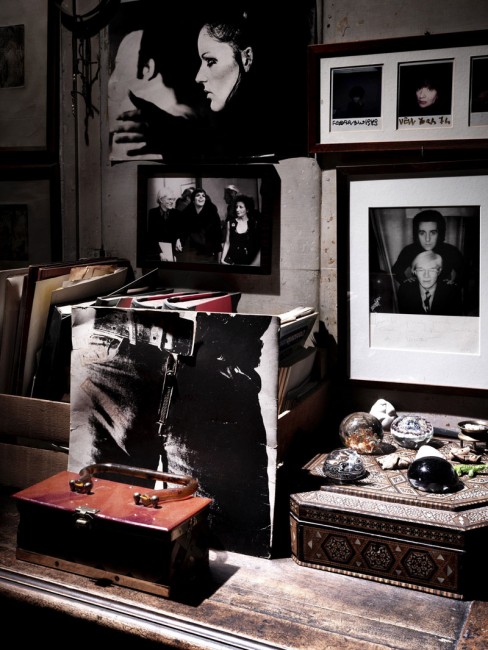

Un universo difficile da decifrare con i soli mezzi della critica artistica. Le sue figure filiformi, le commistioni talvolta macabre e sempre insolite, hanno radici connaturate alla sua vita, in maniera maggiore che in altri artisti. Il volume appena uscito “Carol Rama. Il magazzino dell’anima”, edito da Skira, è un edificante e lodevole tentativo di intromissione benevola all’interno delle confessioni dell’artista, attraverso le testimonianze, le tracce, gli indizi presenti all’interno di casa Rama. Quello che si spalanca sotto la luce artificiale delle lampade domestiche è un ordine all’apparenza intrafugabile, ricolmo di manufatti, arnesi, utensili dalla provenienza più disparata. Le fotografie impeccabili di Bepi Ghiotti – macchina fissa, diaframma chiuso, tempi lunghi di esposizione – lasciano che il trasferimento sul supporto sia identico all’immagine catturata, senza che artifici tecnici intacchino minimamente la verità dell’immagine. Il risultato è un concentrato di malinconia e disarmo, come se la gentile spettralità trafugata dall’interno si posasse lentamente sulla carta stampata, fino quasi a sentirne l’olezzo.

Maria Cristina Mundici, autrice del volume e storica dell’arte, ha frequentato l’artista e la sua “mansarda”, dai vetri oscurati e dalle pareti sfumate di grigio, dagli anni novanta a oggi, al fine di intraprendere un percorso a immagini e parole che restituisca almeno in parte l’orizzonte simbolico delle opere dell’artista.

Perché quella della Rama non è soltanto una dimora o uno studio, ma il luogo in cui vive da settant’anni, accumulando una quantità inimmaginabile di oggetti affettivi, alcuni provenienti dalla famiglia, altri feticci raccattati in ogni dove, altri regalati da amici (tra i quali Man Ray, Carlo Mollino, Andy Warhol, Edoardo Sanguinetti), tutti disposti in un ordine maniacale all’apparenza caotico, come ogni opera d’arte che ne valga l’appellativo.

Nel volume sono eluse intenzionalmente immagini delle opere, a rendere ancora più efficace un approccio quasi narrativo all’esistenza della Rama, tutta raccolta nelle mura domestiche e negli oggetti altrimenti destinati a scomparire con la memoria dell’artista. L’abbandono della biografia artistica convenzionale a favore di uno sguardo più intimo e appassionato trasforma il volume in una sorta di memoriale sottinteso, un diario involontario di una vita riservata e straripante, di marze, spiriti, talento e devozione.

Carol Rama cominciò a dipingere a quattordici anni, senza quasi mai smettere. Ognuno di noi ha una malattia tropicale dentro di sé, che cerca di rimediare. Io rimedio con la pittura, eppure la prima grande retrospettiva arrivò solo nel 1985, a distanza di cinquant’anni dall’inizio della sua carriera pittorica, quando Lea Vergine, con allestimento di Achille Castiglioni, mette in piedi una mostra epocale nel Sagrato del Duomo di Milano. Il tardo riconoscimento pubblico è da iscriversi in un perbenismo antecedente che considerava inaccettabili le sue opere corroborate da parti anatomiche erotiche e sfacciate, con innesti di animali, protesi ortopediche, dentiere, scarpe e altri feticci. Addirittura, nel 1945, la sua prima personale fu bloccata e le opere sequestrate, poiché ritenute inaccettabili per il buongusto dell’epoca. Non solo, una seconda “scomunica” dalla società arrivò perfino nel 2006, quando il Tribunale di Torino pronunciò l’interdizione di Carol Rama nientemeno che per ‘infermità di mente’, a causa dei 38 scatti in cui l’artista posò nuda per l’amico Dino Pedriali (fotografo, fra gli altri personaggi, di Pasolini, Warhol, Nureyev), che risalgono al giugno del 2005 e che avrebbero dovuto essere esposti alla galleria Luxardo di Roma. La mostra fu annullata poiché l’avvocato difensore diffidò la galleria dal mostrare quelle foto “sconvenienti”, nonostante la galleria abbia tenuto a sottolineare più volte che il lavoro di Dino Pedriali rende pienamente giustizia alla grandezza di Carol Rama, alla sua arte e alla sua vita.

Una vita pregna di dolore quella della Rama, le cui opere sono nient’altro che il volto manifesto di un’ira sommersa e indelebile. Il collasso finanziario della famiglia, la vita agiata decaduta, il suicidio del padre, il ricovero della madre in ospedale psichiatrico sono i tragici eventi che segnarono l’esistenza dell’artista e i cui riferimenti nelle sue opere appaiono inoppugnabili, così come sono visibili all’interno delle mura domestiche, adornate di oggetti appartenenti alla memoria familiare: l’Olivetti M.20 del padre, le miriadi di suole, protesi e piedi dell’azienda ortopedica dell’amato zio Edoardo, le foto della madre, quelle degli amici di sempre, le protesi dei denti della zia, gli stracci, i busti, le pietre.

La sensazione di amarezza che pervade gli scatti è la traduzione emotiva di ricordi perpetui, di desideri dissodati, di passioni inestinguibili: “Nella casa di un’artista c’è di più […], perché è previssuta, tormentata e rivisitata in continuazione”, così l’artista a riguardo, per poi aggiungere “[…] noi dobbiamo prepararci a giorni disperati e felici, che poi è uguale in qualche modo, dobbiamo muoverci con disinvoltura, non dobbiamo avere spazi che non sono nostri”. Attorniata da grigie pareti animate, in un volume domestico ricolmo di presenze fissate in oggetti, Carol Rama mangia, dorme, pensa, dipinge. La stessa coerenza compositiva che domina le opere la si riscontra nella disposizione degli oggetti nella casa, “installazione di una vita”. Ma è solo attraverso la pittura che in lei la tragedia volge in forma e il buio esterno in luce interiore.

Laura Migliano

D’ARS year 54/nr 219/autumn-winter 2014 (articolo completo in italiano)

“I hate flowers, perhaps because they are more beautiful than my paintings, more beautiful than me. Because of the anger within me”

Olga Carolina Rama, Torino, 1918: according to the registry office. In her early watercolours she becomes Olgacarolrama, spelt in composed, almost phlegmatic lowercase letters. Within a few years it is simply Carol Rama; a stage name, resolved and dry, which caught the attention of many, from Man Ray to Paolo Poli, who writes “I’ve always liked this name, with its Greek connotations, such as panorama, or Cinerama”. Carol Rama is the outstanding Italian artist of the twentieth century; an eccentric and tenacious woman, a restless visionary who was nonetheless always ardently linked to reality. A reality filtered and circumscribed to her biography, in which ghosts and objects are joined and amalgamated to create a complex, naked and raw imagery.

It is a universe that is difficult to decipher only via artistic criticism. Her threadlike figures, the sometimes macabre and always unusual compositions, are inherently rooted to her life. The book “Carol Rama. The warehouse soul” has just been published by Skira; it is an uplifting and laudable attempt, which benevolently investigates the confessions of the artist through the testimonies and clues that can be found inside the Rama residence.

What we discover inside, underneath the artificial light of domestic light-bulbs, is an almost sacred and unalterable order; full of artefacts, tools and utensils with the most disparate backgrounds. The candid photos by Bepi Ghiotti are not hampered or touched-up with technology, thereby retaining the truth of the original image. The result is a mix of melancholy and disarmament, almost as if the gentle eeriness stolen from inside the shot slowly fused with the printed paper -as if it needed to smell the stench.

Maria Cristina Mundici, an art historian and the author of the book, has visited the artist and her “loft” (with its tinted windows and grey walls) throughout the nineties up until the present day so as to create a journey of images and words that resembles, at least in part, the symbolic horizon of the artist’s works.

Rama’s is not simply a building or a studio, but the place in which she has lived seventy years, accumulating an unimaginable quantity of objects; some deriving from her family, others are fetishes picked up from innumerable places, others were donated by friends (including Man Ray, Carlo Mollino, Andy Warhol, Edward Sanguinetti). All are arranged with obsessive care in a seemingly chaotic order, much like every great art work.

The book intentionally circumvents images of the works, so as to make the narrative approach to Rama even more effective, as she is engulfed in the domestic space and in the objects that would otherwise disappear along with the artist’s memory. The abandonment of the conventional artistic biography in favour of a closer, more intimate and passionate gaze, turns the volume in a kind of memorial, an involuntary diary of a very private and overflowing life, of talent, spirit and devotion.

Rama began painting at fourteen, and hardly ever stopped, “Each of us has a tropical disease within themselves that they seek to cure. I cured mine through the painting.” Yet the first major retrospective arrived only in 1985, after fifty years since she began her painting career, when Lea Vergine, with help of Achille Castiglioni, set up an epochal exhibition in the square in front of the Duomo di Milano. The late recognition by the public is due to its outdated attention to “respectability”, and it therefore shunned her works, which were all corroborated by brazen and erotic anatomical parts, peppered with animals, orthopaedic implants, dentures, shoes and other fetishized items. Indeed, in 1945, one of her first exhibitions was censored: it was shut down and her works were seized, as they were deemed unacceptable and vulgar. Not only that, but a second “excommunication” from society came as late as 2006, when the High Court of Turin pronounced the interdiction of Carol Rama due to her ‘insanity’. This took place because of the 38 shots (dating back to 2005) in which the artist posed nude for her friend Dino Pedriali (photographer, among other characters, of Pasolini, Warhol and Nureyev) and that should have been exposed in the Luxardo gallery in Rome. The show was cancelled because the defence lawyer insisted that the gallery should not show the “inappropriate” photos, despite the gallery repeatedly stressing that the work of Dino Pedriali did full justice the magnitude of Carol Rama, to her art and to her life.

It was life full of pain that of Rama, whose works are nothing but the manifestations of a submerged and indelible anger. The financial ruin of her family, the decadent good life, her father’s suicide, the hospitalization of the mother in a psychiatric hospital are all tragic events that marked the existence of the artist. References to these tragedies appear prominently throughout her works and are visible within the home, which is adorned with objects belonging to the family memory: her father’s Olivetti M.20, the myriad of soles, prostheses and the feet from the orthopaedic company of her beloved uncle Edoardo; photos of her mother, of old friends, the denture of her aunt, rags, busts, and stones.

The feeling of bitterness that pervades the shots is the emotional translation of perpetual memories, of shattered desires and of unquenchable passions: “In an artist’s home there is more […] Because it is tortured and revisited all the time” is what the artist thinks about the matter, before adding, “[…] we must prepare for desperate and happy days […] we have to move casually, we should not have spaces that do not belong to us “. Surrounded by grey animated walls, in a home filled with presences fixed by objects, Carol Rama eats, sleeps, thinks and paints. The same cohesive composition that dominates her works is also found in the arrangement of the objects in her domestic space, “an installation of a lifetime.” But it is only through painting in which she turns tragedy in shape and the dark exterior into inner light.

Laura Migliano

D’ARS year 54/nr 219/autumn-winter 2014 (abstract dell’articolo in inglese)

Acquista l’intero numero in formato epub/mobi oppure abbonati a D’ARS